Fracking’s Wastewater, Poorly Understood, Is Analyzed for First Time

By Zahra Hirji

Researchers determined general chemical footprint of one liter samples, but not relative concentrations, and call for further study.

A new study in the journal Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts offers one of the most comprehensive analyses yet of what’s in a type of waste called produced water, a poorly understood and controversial by-product of fracking.

This peer-reviewed study by a pair of researchers at Rice University in Houston shows that while fracking-produced water shouldn’t be allowed near drinking water, it’s less toxic than similar waste from coal-bed methane mining. It also revealed how the contents of this waste differ dramatically across three major shale plays: Texas’ Eagle Ford, New Mexico’s Barnett and Pennsylvania’s Marcellus.

Fracking involves injecting a slurry of water, chemicals and sand down a well to crack open shale bedrock and extract oil and gas. The study defines produced water as the water that flows out of a well after fossil fuel extraction starts. It includes some of the slurry first injected down a well, as well as naturally occurring water and materials from deep underground, such as salts, heavy metals and radioactive material.

Previous studies have examined the salinity of this waste and even some of the inorganic chemicals. Building from that, the Rice researchers identified 25 inorganic chemicals in the waste. Of those, at least six were found at levels that would make the water unsafe to drink—barium, chromium, copper, mercury, arsenic and antimony. Depending on the chemical, consuming it at high levels can cause high blood pressure, skin damage, liver or kidney damage, stomach issues, or cancer.

But the study’s innovation involved examining and identifying over 50 organic chemicals in the waste—an area that’s been little studied previously. Some of these are potentially dangerous, depending on their concentrations, such as the cancer-causing toluene and ethylbenzene; however, such levels were not provided.

Study author Andrew Barron said the results showed that produced water “was not quite as bad as we thought.”

For example, a related cancer-causing chemical called benzene, which is often seen in oil-and-gas products and waste, was not detected. Moreover, another set of cancer-causing chemicals found in similar wastewater associated with coal-bed methane mining was not observed.

Researchers did not look closely at the waste’s naturally occurring radioactive materials.

Wilma Subra, an environmental consultant from Louisiana, told InsideClimate News in an email that the lack of benzene was “surprising.” Subra, who works extensively in South Texas’ Eagle Ford, added that she would have liked the study to cover radioactive materials, which Texans are especially concerned about.

Cracking the Case

According to the study authors, the most surprising find was the presence of group of organic compounds called halocarbons, some of which are potentially toxic. These chemicals are not native to the geology of the area being drilled; nor are they found in the man-made fluids purposefully injected down a well during fracking.

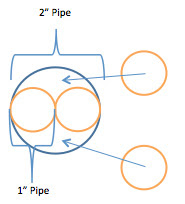

Eventually, the researchers cracked the chemical case and fingered waste treatment as the source. A common type of waste treatment uses chlorine to strip dirty water of bacteria. When this chlorinated water is then injected down a well, it potentially reacts with materials in the local geology to form halocarbons. In other words, researchers found traces of a waste treatment process in pre-treated waste. How does that happen?

To understand, let’s walk through the waste-handling process.

A single fracked well can use over 2 million gallons of water. Instead of constantly relying on freshwater for this, drillers are increasingly treating and then reusing produced water, along with other types of fracking wastewater.

Now imagine that there are two wells: A and B. For Well A, drillers use only freshwater. In the resulting waste, there are no halocarbons. But some of that waste then gets treated with chlorine.

A mix of freshwater and treated water is then shipped to the second site and injected into Well B. According to the researchers, the chlorinated water likely then reacts with the naturally occurring salty water deep underground. This reaction forms entirely new chemicals—halocarbons—that show up in Well B’s waste. Since so many operators are reusing waste at current operations, it makes sense that halocarbons are seen across all the study’s samples, which were collected from wells less than a year old.

Barron, the study author, said the observed levels of these inorganic compounds are minimal and “not a cause for panic.”

At higher levels, however, some of the observed halocarbons—including a type called organobromides, which has been associated with liver damage—could pose a public health risk. And their unanticipated presence indicates that the way wastewater is treated should be reviewed, said Barron, a professor of material science who holds the Welch Chair of Chemistry at Rice. Starting this year, Barron also serves as a scientist at the Energy Safety Research Institute in the United Kingdom, a country looking to expand fracking.

The investigation, which took more than a year, has implications for oil-and-gas operators in water-strapped states such as Texas, which is in the midst of a drought. Such states are increasingly looking to reuse wastewater rather than continually relying on precious fresh water. Just last year, Texas oil-and-gas regulators at the Railroad Commission passed new rules encouraging operators to reuse more of their waste from oil-and-gas drilling.

“What the authors have shown here is interesting and intriguing,” said Lee Ferguson, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Duke University, in Durham, N.C. Ferguson, who was not involved with the research, called it a starting point for further study.

A First Step

The study was funded by the Robert A. Welch Foundation, which supports research in chemistry, and the Ser Cymru programme, a health-and-environment research initiative launched by the Welsh government.

According to Barron, the authors first encountered produced water in their research for the Navy. They were looking at ways to design wetsuits that were salt permeable but impermeable to oil and gas molecules. Their cursory encounter with produced water made them realize there was still a lot to know about it—and that interest grew into this separate analysis.

Wearing gloves, Barron and his colleague, Samuel Maguire-Boyle, gathered produced water samples in specially cleaned one-liter Mason jars from three different well sites in the three different shale regions. At each site, they collected approximately 19 jars of produced water from storage tanks that connect directly to a well.

The report details the analyses of only three sites, one from each shale play. However, Barron noted, samples were collected from a dozen well sites and the three samples covered in the report were representative of that larger survey.

After stripping the water of any solids, the scientists used mass spectrometry to analyze the liquid. This analytical technique provides a unique signal for each targeted compound. The researchers then matched these signals with those from an industry database.

According to Duke’s Ferguson, this method is good for determining a general chemical footprint of a sample but it’s not always exact, because many compounds have similar profiles. To be absolutely confident in their results, he suggested that the researchers perform additional analysis. Moreover, he pointed out that the paper doesn’t provide the relative concentrations of the organic compounds, making it very difficult to determine their levels.

Barron said the group did additional analysis to determine relative levels “within a narrow range,” but he said more samples are needed to confirm them.

Barron hopes to replicate this study eventually at more well sites and determine how the composition of produced water varies within a single shale play.

Source: Inside Climate News.

Pure Water Gazette Fair Use Statement

![pwanniemedium[1]](http://www.purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/pwanniemedium1.jpg)