EPA: GenX Nearly As Toxic As Notorious Non-Stick Chemicals It Replaced

Agency’s Review Comes 12 Years After Industry Began Phaseout of PFAS Compounds

GenX, introduced a decade ago as a “safer” alternative for the notorious non-stick chemicals PFOA and PFOS, is nearly as toxic to people as what it replaced, says an Environmental Protection Agency study released recently.

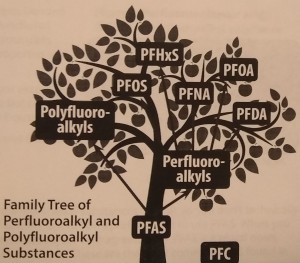

EPA published a draft toxicity review for GenX and a related compound called PFBS, both part of the PFAS family of chemicals. Environmental Working Group’s analysis of EPA’s assessment shows that very tiny doses of GenX and PFBS could present serious health risks, including harm to prenatal development, the immune system, liver, kidney or thyroid.

“It is alarming that, 12 years after DuPont, 3M and other companies, under pressure from EPA, began phasing out PFOA and PFOS, we find that replacements like GenX are nearly as hazardous to human health,” said David Andrews, Ph.D., senior scientist at Environmental Working Group.

“EPA scientists have given us valuable new information here, but the study’s real significance is to show that the entire chemical regulatory system is broken. EPA has allowed hundreds of similar chemicals on the market without safety testing, and it’s urgent that the agency evaluate the risk Americans face from all of these chemicals combined.”

GenX is a successor to PFOA, formerly used by DuPont to make Teflon. PFOA has been linked to cancer in people and to the reduced effectiveness of childhood vaccines and other serious health problems at even the smallest doses. GenX’s chemical structure is very similar to PFOA’s, but it was not adequately tested for safety before being put on the market, in 2009. DuPont has provided test results to the EPA showing that GenX caused cancer in lab animals.

GenX is used to produce non-stick coatings on food wrappers, outdoor clothing and many other consumer goods. A 2017 report by EWG and other groups found the GenX family of chemicals in food wrapping samples from 27 different fast food chains.

“The system has it backwards: Instead of putting the burden of proof on EPA to show that chemicals like GenX are safe, the chemical industry should be responsible for testing its products for safety before they’re put on the market,” said Andrews. “This broken system has enabled DuPont and other companies to contaminate nearly everyone on Earth, including babies in the womb, with these chemicals.”

DuPont’s Deception About Health Risks From Non-Stick Chemicals

In 2001, attorney Robert Bilott sued DuPont on behalf of 50,000 people whose drinking water had been contaminated by PFOA, the carcinogenic compound used to make Teflon at the chemical company’s plant in Parkersburg, W. Va. EWG published a series of investigative reports based on secret documents uncovered in the lawsuit, revealing that DuPont knew about PFOA’s dangers for decades but didn’t tell regulators or the public. EWG filed a complaint with the EPA, which led to a record fine against DuPont. Our research also found that the entire class of non-stick, waterproof chemicals had polluted people, animals and the environment in the most remote corners of the world.

Although PFOA and some related PFAS chemicals have been phased out, they still contaminate the drinking water of an estimated 15 million Americans. The saga of PFOA pollution in Parkersburg and beyond is told in “The Devil We Know,” a documentary available on streaming services.

Source: Environmental Working Group