Iron in Well Water

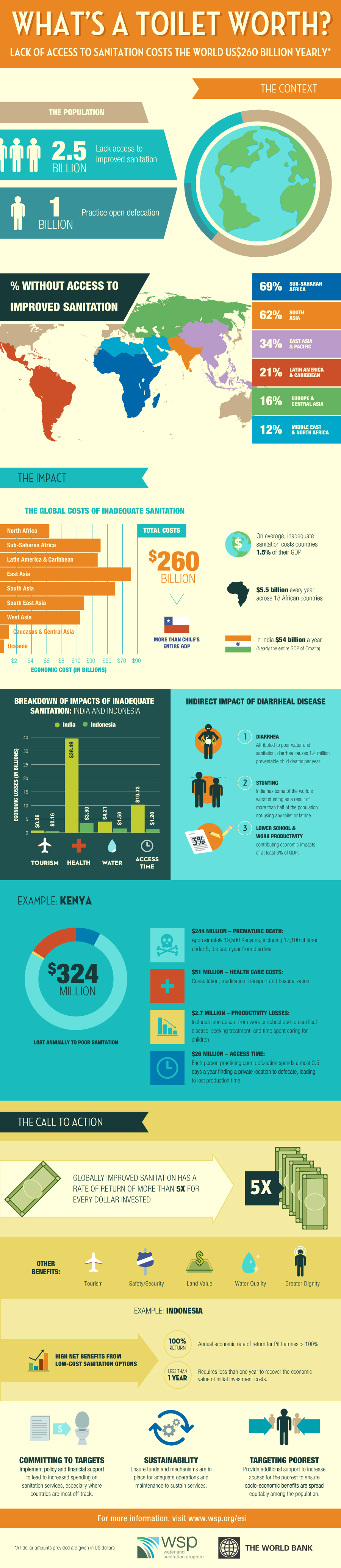

Gazette Introductory Note: Iron is among the most persistent problems faced by residential well owners. It is also among the least understood. The following article from the Minnesota Department of Health website is a concise overview of the iron issue. Our main website, www.purewaterproducts.com, has in-depth information on the treatment of iron by a variety of methods. We also welcome phone or email information requests about treatment of iron issues in residential wells.–Gene Franks, Pure Water Products.

What do these have in common – a taconite mine in northern Minnesota, the color of your blood, a rusty pail, and yellow or red stains on sinks and plumbing fixtures? The answer is – Iron. Iron is the fourth most abundant mineral in the earth’s crust. Soils and rocks in Minnesota may contain minerals very high in iron, so high in fact, that taconite can be mined for its iron content. Iron gives the hemoglobin of blood it’s red color and allows the blood to carry oxygen. The iron in a metal pail turns to rust when exposed to water and oxygen. In a similar way, iron minerals in water turn to rust and stain plumbing fixtures and laundry.

Iron in Well Water

As rain falls or snow melts on the land surface, and water seeps through iron-bearing soil and rock, iron can be dissolved into the water. In some cases, iron can also result from corrosion of iron or steel well casing or water pipes.

Health Concerns

Iron in well water usually does not present a health problem. In fact, iron is needed to transport oxygen in the blood. The human body requires approximately 1 to 3 additional milligrams of iron per day (mg/day). The average intake of iron is approximately 16 mg/day, virtually all from food such as green leafy vegetables, red meat, and iron-fortified cereals. The amount of iron in water is usually low, and the chemical form of the iron found in water is not readily absorbed by the body. Iron bacteria, that may be associated with iron in water, are not a health problem.

Iron may present some concern if certain bacteria have entered a well, since some pathogenic (harmful) organisms require iron to grow, and the presence of iron particles makes elimination of the bacteria more difficult.

Iron Problems

Iron in water can cause yellow, red, or brown stains on laundry, dishes, and plumbing fixtures such as sinks. In

addition, iron can clog wells, pumps, sprinklers, and other devices such as dishwashers, which can lead to costly repairs. Iron gives a metallic taste to water, and can affect foods and beverages – turning tea, coffee, and potatoes black.

Forms of Iron

Iron can occur in water in a number of different forms. The type of iron present is important when considering water treatment. Water that comes out of the faucet clear, but turns red or brown after standing is “ferrous” iron, commonly referred to as “clear-water” iron. Water which is red or yellow when first drawn is “ferric” iron, often referred to as “red- water” iron. Iron can form compounds with naturally occurring acids, and exist as “organic” iron. Organic iron is usually yellow or brown, but may be colorless. Water containing iron bacteria is said to contain “bacterial” iron.

Testing

Yellow or red colored water is often a good indication that iron is present. However, a testing laboratory can determine the exact amount of iron, which can be useful in determining the best type of treatment. In addition to testing for iron, it can be of value to also test for hardness, pH, alkalinity, and iron bacteria. County health departments may offer some of these tests. Private testing laboratories can be contacted about their services and fees. Most advertise in the phone book under “Laboratories-Testing.”

The amount of a dissolved material in water is usually reported as the number of milligrams per liter (mg/L). This is the weight of material in 1 liter (approximately 1 quart) of water. A milligram per liter is approximately equal to 1 part per million (ppm). Iron in amounts above 0.3 mg/L is usually considered objectionable. Iron levels are usually less than 10 mg/L.

Controlling Iron

The most common method for controlling iron in water is water treatment. In some circumstances, another alternative is to use a different water source that is low in iron, such as a public water system or a well drawing water from a different water-bearing formation. In some cases, a new well may be an option, however, it is difficult to predict what the iron concentration will be. Neighboring wells may be an indicator, but the iron content of two nearby wells may be quite different.

Water Treatment

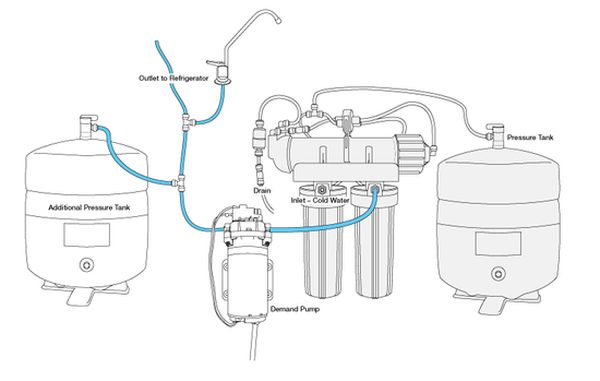

Treatment of water containing iron depends on the form(s) of the iron present, the chemistry of the water, and the type of well and water system.

Clear-water iron is most commonly removed with a water softener. Manufacturers report that some units are capable of removing up to 10 mg/L, however 2 to 5 mg/L is a more common limit. A water softener is actually designed to remove hardness minerals like calcium and magnesium. Iron will plug the softener, and must be periodically removed from the softener resin by backwashing. Also, if the water hardness is low and the iron content high, or if the water system allows contact with air, such as occurs in an air-charged “galvanized” pressure tank, a softener will not work well. Ion exchange water softeners add sodium to the water which may be a concern for persons on a sodium restricted diet.

Red-water iron can be removed in small quantities by a sediment filter, carbon filter, or water softener, but the treatment system will very quickly plug up. A more common treatment for red-water iron and clear-water iron in concentrations up to 10 or 15 mg/L is a manganese greensand filter, often referred to as an “iron filter.” Aeration (injecting air) or chemical oxidation (usually adding chlorine in the form of calcium or sodium hypochlorite) followed by filtration are options if iron levels exceed 10 mg/L.

Organic iron and tannins present special water treatment challenges.Tannins are natural organics produced by vegetation which stain water a tea-color. In fact, the tannins in coffee or tea produce the brown color. When tea or coffee is made with water containing iron, the tannins react with the iron forming a black residue. Organic iron is a compound formed from an organic acid and iron. Organic iron and tannins can occur in very shallow wells, or wells being affected by surface water. Organic iron and tannins can slow or prevent iron oxidation, so water softeners, aeration systems, and iron filters may not work well. Chemical oxidation followed by filtration may be an option.

Well Treatment

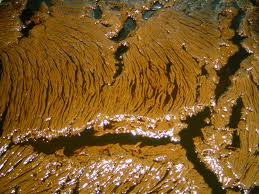

Iron bacteria are organisms that consume iron to survive and, in the process, produce deposits of iron, and a red or

brown slime called a “biofilm.” The organisms are not harmful to humans, but can make an iron problem much worse. The organisms naturally occur in shallow soils and groundwater, and they may be introduced into a well or water system when it is constructed or repaired.

Treatment options for elimination or reduction of iron bacteria include physical removal, heat, and chemical treatment. The most common treatment is “shock” chlorination of the well and water system. See Iron Bacteria in Well Water. Remember, iron bacteria need iron to survive. Eliminating the bacteria will not eliminate the iron – both well treatment for the bacteria, and water treatment for the iron will be needed.

Source: Minnesota Department of Health.

![pwanniemedium[1]](http://www.purewatergazette.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/pwanniemedium1-246x300.jpg)