Why sewers got so costly, complicated

by Dan Horn

Editor’s Note: This description of how modern sewer systems operate should take the sting out of rising charges on your water bill. We really get a lot for our money. We’ve cut off the final part of the article which consists of a chronology of the rising costs of Cincinnati sewerage costs. You can read the full article at Cincinnati.com. I also took the liberty to add a couple of pictures to Mr. Horn’s article.–Hardly Waite.

Running a sewer system used to be so simple.

Connect a pipe to a building. Connect that pipe to a bigger pipe. Make sure it all flows downhill.

A federal court ruling here two weeks ago showed just how much that’s changed and how complicated the business of sewers has become in the 21st century.

The decision, which set rules for hiring contractors at Hamilton County’s sewer district, described an increasingly complex industry that now requires far more than gravity and a good pipe.

Anyone who washes dishes or flushes a toilet is paying for that new complexity through skyrocketing sewer rates. And anyone who cares about the health of the region’s rivers and streams is watching closely to see how the sewer district adapts to this complicated new world.

The Metropolitan Sewer District today is a sprawling, heavily regulated behemoth with almost 700 workers, 3,000 miles of sewers and a mandate to spend more than $3 billion on new construction.

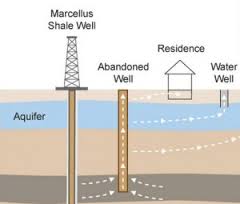

Most city sewers are designed so that gravity alone carries wastewater to the treatment plants. However, sometimes low-lying areas like valley locations need pumping plants to push wastewater through pipes. A modern city often has to operate several pumping plants.

While the district is busy doing what it’s always done – digging trenches and burying pipe – it’s also immersed in environmental regulations, court orders, politics, labor conflicts and new “green” technology that powers buildings with methane captured from waste.

It’s a far cry from the 1950s and ’60s, when waste treatment was in its infancy and moving the stuff in the pipes from homes to the river was the main objective.

“It was a sleepy little utility,” said Hamilton County Administrator Christian Sigman. “Things are different now.”

So how did it get this way?

Like the sewer district itself, it’s complicated. But here are three big reasons:

Growth in suburbs means more waste

For most of the 20th century, Cincinnati ran its own sewer system, while a patchwork of smaller systems handled sanitary waste throughout Hamilton County. It was confusing and inefficient and sometimes, quite literally, smelly, but it worked well enough.

By the 1950s, though, the gradual outward push of Cincinnati’s population began. New homes started popping up in the suburbs, and local sewer systems quickly became inadequate. Something had to give. So in 1968, city and county officials cut a deal: The county would take charge of a regional sewer district, and the city would oversee day-to-day operations.

The Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati was born.

The arrangement made sense for both sides because the county needed a reliable, uniform system to encourage development, and the city had already signed contracts with smaller communities to handle their wastewater.

Geography played no small part, too. Because Cincinnati sits in a valley alongside the Ohio River, most of the waste from the suburbs was sure to find its way here eventually.

“Gravity knows no political boundaries,” Sigman said.

Other cities were doing the same thing. Some, like Cincinnati, focused mostly on their home county. Others, like Cleveland and Milwaukee, took a more regional approach and involved several counties.

“They evolved differently,” said Adam Krantz, managing director of government affairs for the National Association of Clean Water Agencies. “There is no one-size-fits-all pattern.”

Although the structure of the new district made sense at the time, the deal planted the seeds of future problems. It didn’t matter in the 1960s that the city and county weren’t clear about who had final say on construction or hiring contractors. Everyone just did what needed to be done.

It would matter quite a lot when costs, regulations and legal problems began to escalate in the 1990s.

Public demands cleaner water, environment

The environmental movement of the 1970s changed the game for sewer districts across the country, and Hamilton County was no exception.

“What we used to do wasn’t adequate,” said Rob Richardson Jr., a market representative for the Laborers-Employers Cooperation Education Trust, which deals with contractors and workers who do sewer projects. “We had to stop the pollution. We had to fix the problem.”

Maintenance holes, often called man holes, give city workers access to the sewers for periodic inspection and repairs. The city of Los Angeles’ wastewater collection system contains some 140,000 maintenance holes.

The big problem here was “combined sewer overflows,” which occur when heavy rain overwhelms old sewer lines and causes storm and sanitary sewers to mix. The result was a nasty blend of raw sewage and stormwater flowing into creeks, the river and, in some cases, the basements of unhappy homeowners.

That might have been tolerated 100 years earlier. Not anymore. Not after the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, approval of the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the rise of activist groups like the Sierra Club.

People expected more from the sewer district. So federal standards got tougher and treatment plants got better and more complicated. Technology improved and so did the expertise of wastewater engineers.

Still, the sewer district couldn’t keep up with the stricter rules or the decay of a system that was more than 150 years old in some stretches. By 2006, the district was under orders from a federal judge to clean up its overflows and repair its sewers at a cost of more than $3 billion.

Instead of managing a bunch of sewer pipes, then, the district found itself in charge of the largest construction project in county history. Before it’s over, the work will cost more than six times what it cost to build Paul Brown Stadium.

To make matters worse, federal money that once covered large portions of environmental-related work was drying up fast. The sewer district’s executive director, Tony Parrott, said that money might have covered as much as 70 percent of project costs 40 years ago. Today, it covers almost nothing.

“It’s a lot tougher now,” Parrott said. “We’re having to do it in an era when we don’t have any federal grant subsidy, so the true cost falls on the backs of ratepayers. It makes it tougher financially, and it makes it tougher politically.”

Rising sewer costs raise political stakes

The shortcomings of the original 1968 deal emerged in the 1990s and, even more, in the past decade as policymakers in the city and county grappled with the enormous sewer bill coming due.

Suddenly, disagreements couldn’t be resolved with a phone call or a handshake. Billions of dollars were at stake, and sewer bills were climbing fast. The average user now pays almost $800 a year in sewer rates.

“No one wants to see sewer rates go up,” Parrott said, “but it’s a Catch-22. You have to do it.”

Disputes between the city and county over how to manage the district’s expanding and expensive responsibilities landed them in court and halted work on projects for more than a year. The ruling two weeks ago tossed out a city plan, known as “responsible bidder,” that made training programs mandatory for contractors and, critics say, penalized nonunion companies.

The case was bigger than that, though. It also clarified the relationship between the city and county as it relates to the old 1968 agreement. The bottom line: The city runs the district, but the county is the boss.

The fight isn’t over, however, and the two sides are still trying to figure out how to work together. Just last month, county officials said lax project management by the city could lead to big cost overruns.

“It’s a slow-speed crash,” said Commissioner Greg Hartmann. “We can see the iceberg, but we’re still heading for it.”

In just four years, the city and county won’t have any choice. The 1968 agreement expires then, and policymakers will have to hash out a new deal.

Odds are good it will be more complicated than the first one.

Source: Cincinnati.com.

Pure Water Gazette Fair Use Statement