Hopes climb amid talks to clean contaminated ‘Mt. PCB’ in Kalamazoo

By Keith Matheny

Gazette Introductory Note

The article below gives a fine picture of the efforts of Kalamazoo citizens to get rid of “Mt. PCB,” a massive pile of toxic trash left behind when a wealthy corporation pocketed its profits and moved away. This story repeats itself again and again across the nation. Such toxic trash dumps are supposed to be cleaned up by the EPA “Superfund.” The Superfund was initially effective because it had money. Its funds came, logically and sensibly, from a corporate income tax and excise taxes on hazardous substances like petroleum and chemicals. When funding for the Superfund expired in 1995, Congress did not renew it. Instead, we now have a “plan” that funds cleanups like the Kalamazoo PCB mess by the largesse of a stingy Congress and by attempting to collect the money from “primary responsible parties.” The “responsible parties” part usually involves more litigation than cleanup and leaves locals with the trash and the tab. In short, we’ve created another opportunity for corporate welfare where the rich reap the benefits and avoid the cleanup while taxpayers are stuck with the bill.–Hardly Waite.

KALAMAZOO — John DeKoff lives only a few hundred yards from a mound of 1.5 million cubic yards of potentially carcinogenic, toxic material. And he prefers it stay right where it is.

“I want it left alone,” he said of the nearby hill — visible over his shoulder in his backyard — made of materials contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, chemicals used in paper recycling and other industrial processes and known to cause cancer in both animals and humans.

“PCBs attach themselves to the soil,” DeKoff said. “When you start digging into it and moving it around, it dries up and blows in the form of dust. I think a worse short-term problem would be dust, getting it in the air.”

Many of DeKoff’s neighbors have a different view. They want what one called “Mt. PCB” out of the neighborhood as soon as possible. Every

few houses nearby has a yard sign reading: “Message to EPA: Cleanup, not coverup.”

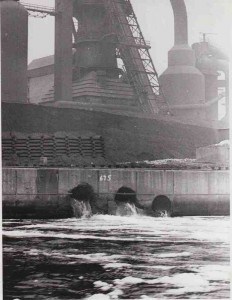

The mound is at the location of the former Allied paper mill on the banks of Portage Creek, about a mile south of downtown Kalamazoo. It was one of several former paper mills in the area that for decades in the 20th century let their untreated wastes flow downstream, eventually into the Kalamazoo River and on into Lake Michigan.

The years of unabated pollution from Allied and other paper companies created one of the nation’s largest EPA Superfund sites, an 80-mile stretch of the Kalamazoo River from west of Battle Creek to Saugatuck on shores of Lake Michigan.

Some residents say the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency previously considered the Allied site only as a temporary holding spot for PCB-contaminated paper wastes until a long-term disposal site was determined. But now the EPA is considering making the Allied landfill the permanent home of the PCBs, as removing them to an approved landfill might cost more than $300 million by their estimates.

“We knew it was dirty, stinky, that sort of thing,” said Jim Reibel, who’s lived nearby since 1956. “But nobody had any idea it was poisonous.”

‘We have a mess’

EPA officials are expected soon to announce a preferred alternative for dealing with the Allied site through release of a feasibility study.

James Saric, EPA’s on-site coordinator for the cleanup effort, said in early May that the study would be released “probably in a month or two.” The EPA did not respond last week to a request for an update.

Allied neighbors say the EPA’s decision could set a precedent for needed decontamination efforts along the rest of the river and elsewhere, with EPA choosing the least expensive and not necessarily the best solution for those living nearby.

“We’re saying, ‘Clean it up. And you people in other parts of the country, you watch what we’re doing, because they will probably do this to you,’ ” said Sarah Hill, a professor of anthropology at Western Michigan University, local resident and member of the Kalamazoo River Cleanup Coalition, a group of community residents seeing a full restoration of the polluted areas near their homes.

Complicating matters, dams along the river allowed PCBs to accumulate behind them over decades. Several of the dams were partially or completely removed in recent years, as they were no longer being used for power generation or other purposes. That’s led to changed river flows that are eroding river banks loaded with PCB contaminants, re-polluting the river.

“We have a mess, and it’s a big project for cleanup,” said Jeff Spoelstra, sustainability coordinator for Western Michigan University.

The Michigan departments of Environmental Quality and Community Health have issued fish eating advisories for fish caught on the Superfund segment of the Kalamazoo River, saying women and children should avoid eating various fish species from the river such as bass, carp and catfish, depending on the location where they were caught.

Hope for a tailor-made solution

Nearly a quarter-century of Superfund remediation costing more than $65 million has only put a dent in the problem. By some estimates, the cost of a thorough remediation will top $2 billion.

Who will foot that bill is uncertain, as holding responsible the perpetrators of the mess is proving elusive. After trading hands multiple times, the company that last owned Allied Paper Inc., Millennium Holdings LLC, a division of Lyondell Chemical Co., went bankrupt in 2010. The company was ordered to provide $50 million for cleanup of the Allied site and another $50 million for cleanup elsewhere along the Kalamazoo River.

“It’s lunacy to think that would pay for it all,” Hill said.

As other contamination hotspots on the river were resolved through capping materials with plastic, clay and earthen layers and leaving them in place, and because such a remedy would fall within the $50 million available from the Allied bankruptcy, many in the community expect that’s the plan that’s coming from EPA for the Allied site.

But city officials don’t accept that as a solution.

“It’s not going to happen here,” Kalamazoo Mayor Bobby Hopewell said. “They need to listen to us, how we do things differently here, and find other solutions. Just because you’ve done this in the past, let’s learn from our past.”

Bruce Merchant, the city’s recently retired director of public services who continues as a Kalamazoo consultant, said city officials have significant concerns about the Allied pile’s proximity to groundwater and Portage Creek. EPA testing has shown no contamination leaching into the groundwater, but that doesn’t mean it won’t happen eventually, Merchant said.

“This site is within a half-mile of our largest well group for the city of Kalamazoo, servicing about 120,000 residents of Kalamazoo County,” he said.

Ironically, anyone filing for regulatory permission from EPA to create a toxic landfill at the Allied site to store PCBs would be rejected “because it sits on top of an aquifer; because it sits next to a creek; all kinds of things that would violate its own rules,” Hill said.

The EPA’s delay in releasing a feasibility study for the Allied site, as well as the agency’s willingness to meet with officials from The Environmental Quality Co., are positive developments, Hopewell says. Environmental Quality Co. officials have indicated they can remove the Allied materials and take them to their specialized landfill off I-94 near Belleville for more than $100 million less than EPA has projected.

“(EPA) haven’t said that these poisons are going to be removed, but they have been moving a little differently than they normally do,” Hopewell said. “That gives me all kinds of hope.”

Many options, but limited funds

Further downriver, in Allegan County, some question the fight to remove the Allied landfill.

“If they get the kind of cleanup they want, it could jeopardize a meaningful cleanup downstream,” said Dayle Harrison, Saugatuck area resident and president of the nonprofit Kalamazoo River Protection Association.

There’s a limited amount of money available, and areas from Plainwell downstream are “almost completely contaminated” with PCBs, he said. Money could best be spent at the Otsego, Trowbridge and Allegan city dams, where the toxins have accumulated, he said.

But the Allied area residents’ fight — which has garnered support from Michigan’s Democratic U.S. Sens. Carl Levin and Debbie Stabenow as well as Republican U.S. Rep. Fred Upton — is using up political capital, energy and time, Harrison said.

Hill, of the Kalamazoo River Cleanup Coalition supporting the Allied landfill’s removal, said instead of bickering over insufficient cleanup funds, citizens should push for a reinstatement of the taxes that once supported Superfunds.

The Superfund trust fund was initially funded through excise taxes on petroleum, chemicals and other hazardous substances, and an environmental corporate income tax. Those taxes expired in 1995, and the program has since been funded through general revenues and the elusive chase of “primary responsible parties.”

“When we start nickel-and-diming cleanup, we are fighting with each other on things we should be unifying about across the country, going to our elected representatives and saying put more money into the system,” she said.

Source: Detroit Free Press.