Sierra rises, quakes erupt as Central Valley aquifer drained

by David Perlman

Are We Creating Earthquakes by Overuse of Water?

The Sierra Nevada is rising.

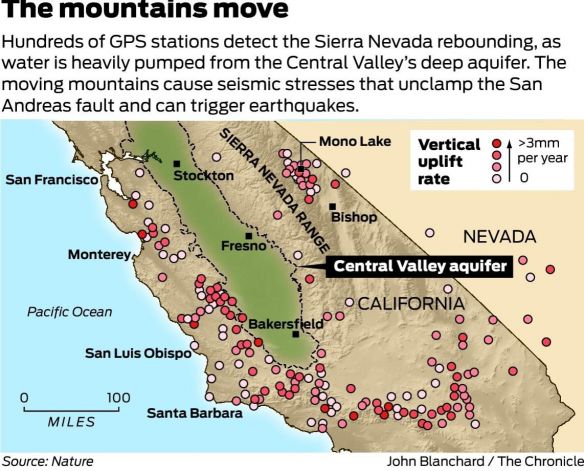

Drought-stricken farmers in the Central Valley are pumping more and more water from the valley’s huge aquifer beneath them, and the drainage is triggering unexpected earthquakes along the San Andreas Fault, scientists have discovered.

For the past 150 years, they report, periodic pumping from the aquifer has caused the towering Sierra to rebound upward as much as 150 millimeters, or about 6 inches. At the same time, they note, California’s Coast Range, which spans 400 miles from Humboldt to Santa Barbara counties, has grown, although by much less.

The pace of uplift in the Sierra is measured only in millimeters, but when California experienced bone-dry seasons between 2003 and 2010 and pumping increased up and down the Central Valley, the High Sierra rose by about 10 millimeters, the geophysicists say. That’s nearly half an inch during those seven years alone.

During that same period of increased pumping, instruments at Parkfield in Monterey County detected unusual clusters of earthquakes along the quake-prone San Andreas Fault there.

The unexpected links between the periodic drainage of the Central Valley’s aquifer and the rise of the mountains that increase stresses on the San Andreas fault zone are reported in the May issue of the journal Nature.

Its authors are a team of Earth scientists led by Colin Amos of Western Washington University and includes Roland Bürgmann of UC Berkeley and William Hammond of theUniversity of Nevada in Reno.

GPS sensitivity

The remarkable ability to measure tiny changes in the height of mountains is made possible by the extraordinary sensitivity of advanced global positioning systems, similar in principle to the GPS devices that tell car drivers where they’re going in unfamiliar cities, block by block.

Hammond and his colleagues at the Nevada Seismological Laboratory regularly analyze signs of the Earth’s movements from more than 12,000 GPS stations around the world. For this study, the team focused on 566 stations in California and Nevada.

“The whole Earth is elastic,” Hammond said, “and when it moves even slightly we can measure it.”

Amos, the study’s lead author, explained the connections.

“As winter snows melt and rains fill the aquifer each year, the enormous weight of the water pushes the Earth’s crust downward beneath both the valley and the mountains,” he said. “Then as pumping drains the aquifer, particularly in dry years, the crust springs upward – mountains, valleys and all – and the rocks rebound like elastic.”

Amos calculated that the amount of water pumped from the great aquifer since 1860 would be enormous, weighing roughly 175 billion tons, more than enough to fill Lake Tahoe.

‘Real eye-opener’

“The periodic stress on earthquake faults would be very small, but in some circumstances even such small stress changes can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” Bürgmann said. “The stresses from the rebounding mountains would give just that extra force needed to unclamp the (San Andreas) fault and encourage, not only small earthquakes, but also larger ruptures to occur.”

“This is a real eye-opener,” said James Famiglietti, a water resource expert and director of the UC Center for Hydrologic Modeling at UC Irvine who has long studied the great aquifer’s long-term drainage issues and its seasonal water losses. He called the study’s conclusions surprising and valid.

“The whole role of fluids and seismicity is still poorly understood. They have identified a real link between human activity and earthquakes,” said Famiglietti, who was not part of the study.

“It forces us to consider not only the role that large groundwater mass changes can play in earthquake frequency, but by extension, the roles of water management decisions in times of drought and climate change.”

Source: SFGate.